Designing Software with Visuals First: An Outside-In Approach

In the competitive landscape of software development, creating applications that stand out and provide exceptional user experiences is crucial. Traditionally, software design often began with a focus on functionality and underlying architecture, with visuals considered later in the development process. However, a growing trend is shifting the focus to “designing from the outside in,” where the visual and user experience elements take precedence. This approach emphasizes the importance of visuals and user interface (UI) in shaping software development, ensuring that the end product not only functions well but also delights users. In this article, we will explore the principles, benefits, and strategies of putting visuals first in software design.

The Shift to Visual-Centric Design

Traditionally, software design was driven by technical requirements, with user interface design often relegated to a secondary role. However, the rise of user-centric design methodologies has highlighted the importance of visual appeal and usability in software development.

Key Points:

- User Expectations: Modern users have high expectations for intuitive, aesthetically pleasing interfaces. Visual appeal directly impacts user satisfaction and engagement.

- Competitive Advantage: A visually appealing design can differentiate software in a crowded market, attracting and retaining users.

- Accessibility: A focus on visuals also involves ensuring accessibility, making the software usable for people with varying abilities.

Principles of Visual-Centric Design

Designing software with a focus on visuals involves several key principles that guide the creation of user interfaces that are both functional and appealing.

Key Principles:

- Simplicity and Clarity:

- Minimalism: Emphasize simplicity by removing unnecessary elements and focusing on essential features. A clean design helps users navigate and interact with the software more effectively.

- Clarity: Use clear visual hierarchies to guide users’ attention and make key actions and information easily accessible.

- Consistency:

- Design Patterns: Employ consistent design patterns and visual styles throughout the software to create a cohesive experience.

- Brand Identity: Ensure that the design reflects the brand’s identity and values, enhancing recognition and trust.

- Visual Hierarchy:

- Emphasis: Use size, color, and placement to emphasize important elements and create a clear visual hierarchy.

- Contrast: Utilize contrast to differentiate elements and improve readability, making sure that users can easily distinguish between interactive and non-interactive components.

- User Feedback:

- Interactive Elements: Provide visual feedback for interactive elements such as buttons and forms to inform users of their actions.

- Error Handling: Design error messages and validation prompts to be clear and visually distinct, helping users understand and correct issues easily.

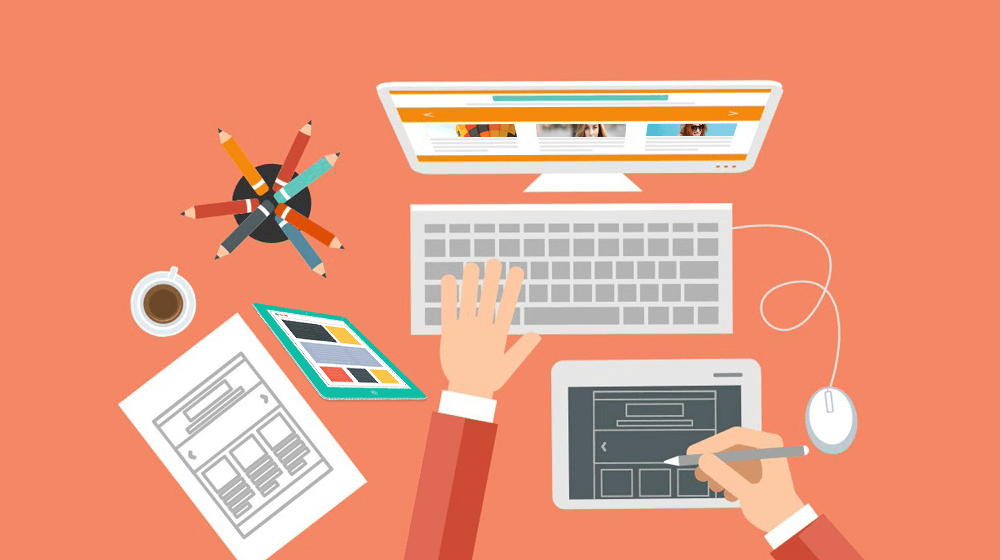

The Role of Prototyping and Wireframing

Prototyping and wireframing are crucial steps in a visual-centric design approach, allowing designers to create and test visual concepts before committing to full development.

Key Points:

- Wireframes:

- Purpose: Wireframes provide a low-fidelity visual representation of the software’s layout and structure, focusing on the placement of elements and overall flow.

- Feedback: Use wireframes to gather early feedback from stakeholders and users, refining the design based on their input.

- Prototypes:

- High-Fidelity Prototypes: Create high-fidelity prototypes to simulate the look and feel of the final product, allowing for more realistic user testing and interaction.

- Iterative Design: Use iterative design processes to refine prototypes based on user feedback and usability testing.

Integrating Visual Design with Functionality

While visuals are critical, they must be integrated seamlessly with functionality to ensure a cohesive and effective user experience.

Key Points:

- Collaboration:

- Design and Development: Foster collaboration between designers and developers to ensure that visual designs are implemented accurately and effectively.

- Feedback Loops: Establish feedback loops to address any issues or adjustments needed during development, ensuring that visual and functional aspects align.

- Usability Testing:

- User Testing: Conduct usability testing to evaluate how well the visual design supports user interactions and tasks.

- Iterative Improvements: Use insights from usability testing to make iterative improvements, enhancing both visual appeal and functionality.

The Impact of Visual Design on User Experience

Visual design plays a significant role in shaping the overall user experience (UX) of software, influencing how users perceive and interact with the application.

Key Points:

- First Impressions:

- Initial Impact: The visual design creates the first impression of the software, influencing users’ perceptions and their willingness to engage further.

- Engagement: A visually appealing design can increase user engagement, encouraging users to explore and use the software more extensively.

- Emotional Response:

- Aesthetics: The aesthetics of the design can evoke emotional responses, such as trust, satisfaction, or frustration, impacting overall user satisfaction.

- Brand Perception: Consistent and high-quality visual design reinforces the brand’s image and values, contributing to positive brand perception.

Best Practices for Visual-Centric Software Design

To effectively implement a visual-centric design approach, consider the following best practices:

Key Practices:

- User-Centered Design:

- Empathy: Understand and prioritize users’ needs, preferences, and pain points to create a design that resonates with them.

- User Research: Conduct user research to gather insights and inform design decisions, ensuring that the visual design aligns with users’ expectations.

- Design Systems:

- Component Libraries: Develop design systems and component libraries to maintain consistency and streamline the design process.

- Guidelines: Create guidelines for visual elements, including colors, typography, and spacing, to ensure cohesive and uniform design.

- Responsive Design:

- Adaptability: Design with responsiveness in mind, ensuring that the visual design adapts to different screen sizes and devices.

- Testing: Test the design across various devices and resolutions to ensure a consistent and functional experience.

- Performance Considerations:

- Optimized Assets: Optimize visual assets, such as images and graphics, to minimize load times and improve performance.

- Efficient Code: Collaborate with developers to ensure that the visual design is implemented efficiently and does not negatively impact performance.

Case Studies: Successful Visual-Centric Software Design

Examining case studies of successful visual-centric software design can provide valuable insights and inspiration for your own projects.

Key Examples:

- Apple’s iOS Design:

- Design Philosophy: Apple’s iOS design emphasizes simplicity, elegance, and user-friendly interfaces, setting a high standard for visual design in software.

- Impact: The visual design of iOS has contributed to its widespread adoption and user satisfaction.

- Slack’s User Interface:

- Design Approach: Slack’s user interface focuses on clarity, organization, and ease of use, with a visually appealing and intuitive design.

- Impact: The visual design of Slack enhances user productivity and engagement, contributing to its success as a communication platform.

Conclusion

Designing software from the outside in, with a focus on visuals, represents a shift towards creating applications that not only function effectively but also provide exceptional user experiences. By prioritizing visual design, applying key principles, and integrating aesthetics with functionality, developers can create software that stands out in a competitive market and delights users. Embracing this approach ensures that visual design becomes an integral part of the software development process, resulting in products that are both visually appealing and highly functional. As the digital landscape continues to evolve, putting visuals first will remain a vital strategy for achieving success in software design and development.